What Is Passive Solar Energy? Home and Building Design, Pros, Cons, and Diagrams

Passive solar energy uses building design to manage sunlight for heating and cooling through orientation, glazing, thermal mass, shading, and ventilation. I defines passive solar systems with examples, then walks through a load-first home workflow: cut heating and cooling loads, confirm south solar access (±30° of true south, unshaded 9 a.m.–3 p.m.), size south glazing with simple planning ratios (about 7% start, 12% direct-gain cap, 20% total passive cap), and choose window performance by climate using U-factor and SHGC.

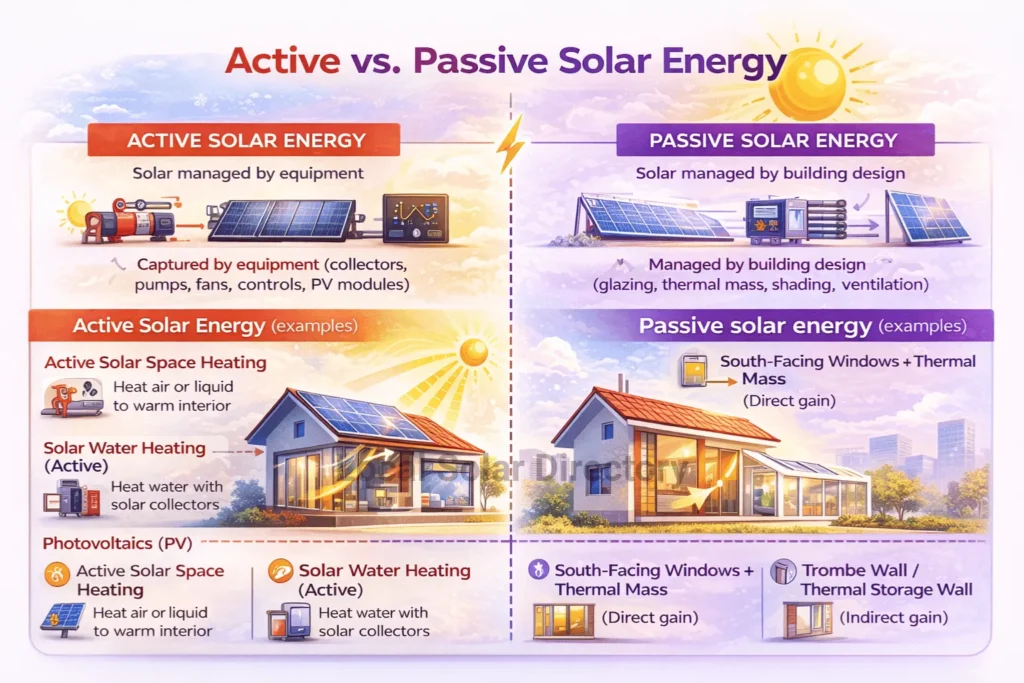

Then i explain the same ideas to commercial and institutional buildings, explains what changes (higher internal gains, deeper floor plates, more glare control and zoning), summarizes measured research impacts, and lists common building elements like façade zoning, perimeter daylighting, thermal mass, and night flushing. At last, I covers pros and cons, components and configurations (direct, indirect, isolated gain), and clarifies passive vs. active solar energy and how solar thermal differs from passive solar design.

What Is Passive Solar Energy?

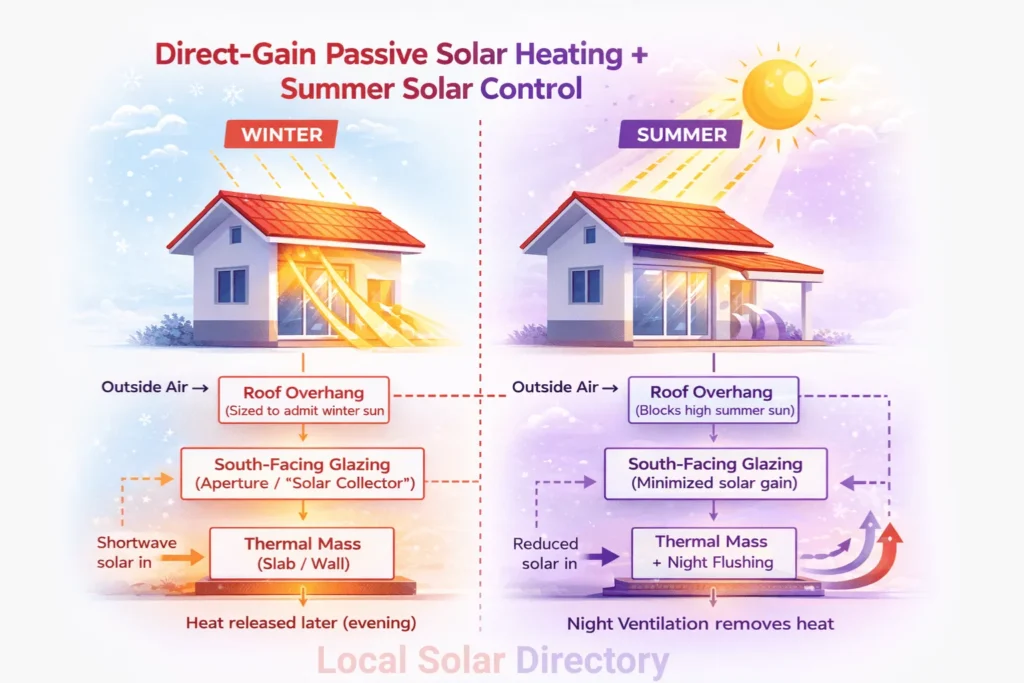

Passive solar energy is solar energy managed by building design—site, orientation, glazing, thermal mass, shading, and ventilation—to reduce heating and cooling energy use without relying primarily on powered devices to collect and move heat. The U.S. Department of Energy (Energy Saver) describes passive solar design as using a building’s site, climate, and materials to minimize energy use, and meeting reduced heating/cooling loads partly with solar energy.

In Diagram 1, winter solar radiation enters through south-facing glazing, warms interior surfaces, and is stored in thermal mass (concrete, brick, stone, tile, or water/phase-change materials). The same façade is protected in summer by solar control (overhangs and shading). DOE also notes that well-designed passive solar homes provide comfort in the cooling season using nighttime ventilation.

Diagram 1 (reference): Direct-gain passive solar heating + summer solar control (simplified)

WINTER (low sun angle) SUMMER (high sun angle)

\ \ \ \ | /

\ \ \ \ | /

\ \ \ \|/

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐

│ Roof overhang │ │ Roof overhang │

│ (sized to │ │ (blocks high │

│ admit winter │ │ summer sun) │

└───────┬─────────┘ └───────┬─────────┘

│ │

Outside air → ┌──────────────────┴─────────────────┐ ┌────────────┴────────────┐

│ South-facing glazing │ │ South-facing glazing │

│ (aperture / “solar collector”) │ │ (minimized solar gain) │

└──────────────────┬─────────────────┘ └────────────┬────────────┘

│ shortwave solar in │ reduced solar in

v v

┌─────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ Thermal mass │ │ Thermal mass │

│ (slab / wall) │ │ + night flushing │

└─────────┬───────────┘ └─────────┬───────────┘

│ stores heat daytime │ stores less heat

v v

Heat released later (evening) Night ventilation removes heat

Passive solar energy systems are passive solar building strategies that use building components as the “system,” including:

- Direct gain: sunlight enters the occupied space and is stored in floors/walls.

- Indirect gain: sunlight heats a storage element (for example, a Trombe wall) that then releases heat indoors.

- Isolated gain: sunlight is collected in a separate space (for example, a sunspace) that can be opened/closed to the main building.

“Passive energy gain” in buildings usually refers to solar heat gain that enters through glazing and reduces the need for mechanical heating, if glazing area, solar access, thermal mass, and controls are balanced. DOE calls the share of heating load met by passive solar design the passive solar fraction.

How Does Passive Solar Home Design Work?

Passive solar home design works by collecting winter sun through properly oriented glazing, storing heat in thermal mass, distributing that heat naturally, and controlling solar gains and ventilation to prevent overheating. DOE explains this in simple terms as heat collection through south-facing windows and retention in thermal mass, then using nighttime ventilation for cooling-season comfort.

Elements of a passive solar home (the parts that must work together)

DOE lists basic elements that must work together for success. These are the practical design elements most homes use:

- Energy efficiency first: insulation + air sealing reduce loads before adding solar features.

- Solar access and orientation:

- South-facing collectors (windows) typically face within 30° of true south.

- Heating-season solar access should avoid shading (DOE describes avoiding shading from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m.).

- Glazing size and placement: more glazing increases solar heat gain but also increases overheating risk if mass and shading are insufficient. DOE warns against oversizing south glass in modern low-load homes and emphasizes proper shading.

- Thermal mass: dense materials absorb solar heat during heating season and absorb indoor heat during cooling season. DOE lists common mass materials (concrete, brick, stone, tile) and notes water and phase-change products can store heat efficiently.

- Heat distribution: conduction, convection, and radiation move heat from collection/storage areas to other rooms.

- Control strategies: overhangs, shading, vents, dampers, and interior shading reduce unwanted gains; DOE also notes some designs use thermostats that trigger fans.

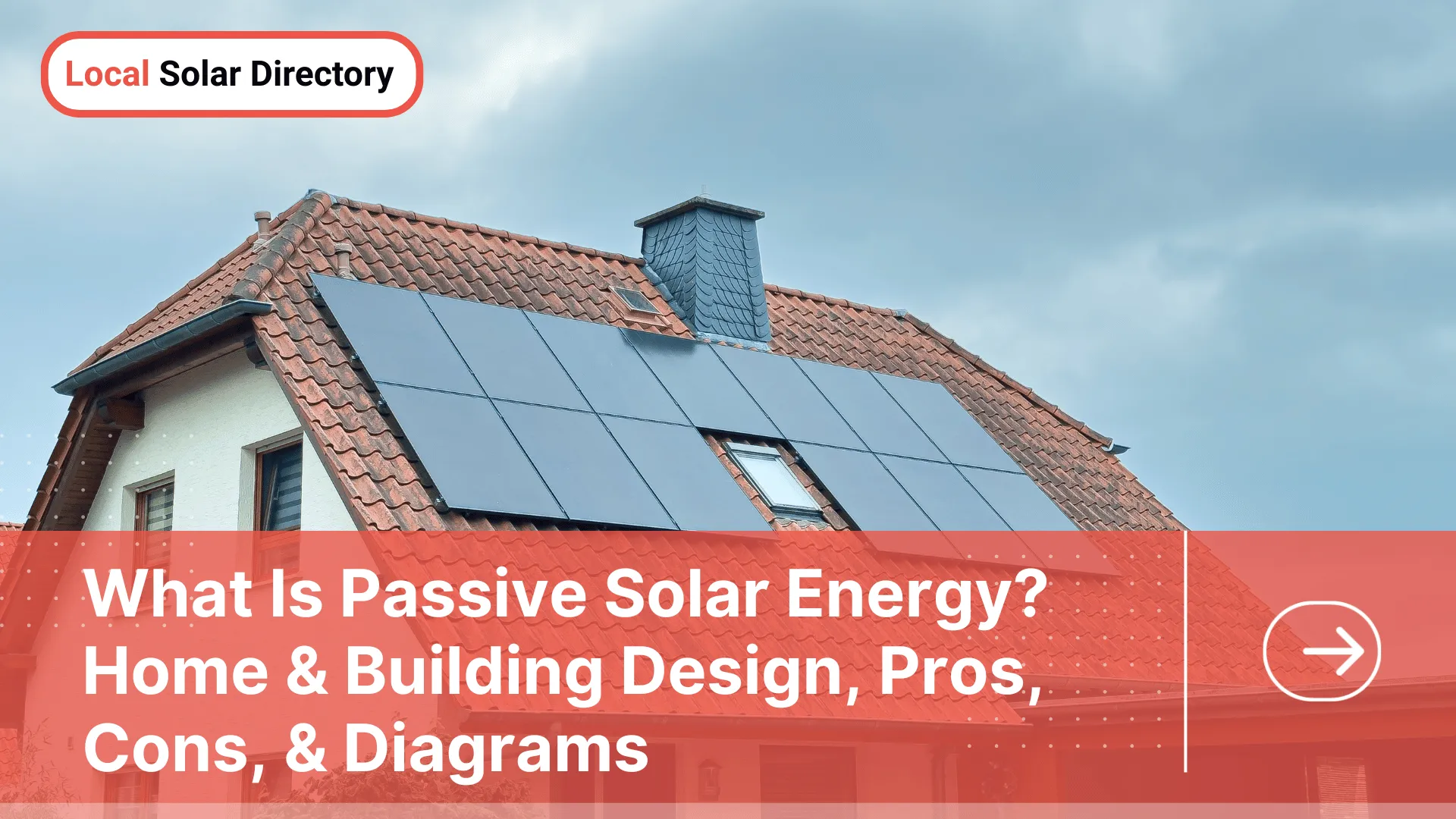

A home-design workflow (steps with measurable design checks)

To design a passive solar home, use a load-first workflow that keeps glazing and thermal mass in balance.

- Reduce heating and cooling loads first

To reduce loads, prioritize air sealing, insulation continuity, and efficient windows. DOE states energy efficiency is the most cost‑effective strategy to reduce heating and cooling bills before adding solar features. - Confirm solar access and basic orientation

To confirm solar access, preserve a clear southern exposure and aim collector glazing within ±30° of true south. DOE also recommends keeping south windows unshaded during heating season (9 a.m.–3 p.m.). - Size south-facing glazing using floor-area ratios

To size south-facing glazing, start with conservative ratios and increase only when thermal mass and controls support it.

You can see in image as well.

NREL’s “Passive Solar Design Strategies” guideline (Portland, Oregon) provides practical ratios for direct gain systems:

- Start with a direct gain glazing area ≈ 7% of total floor area, using the home’s “free mass” (typical construction and contents) to buffer heat.

- For direct gain passive solar houses, the guideline gives a maximum south-facing glazing of 12% of total floor area, independent of added mass, to reduce issues such as glare and fading.

- The guideline also states total passive solar systems combined (direct gain + sunspace, etc.) should not exceed 20% of total floor area to reduce overheating risk.

Example (1,500 ft² house)

- 7% starting point: 0.07 × 1500 = 105 ft² of direct-gain south glazing

- 12% direct-gain cap: 0.12 × 1500 = 180 ft² of direct-gain south glazing

- 20% combined cap: 0.20 × 1500 = 300 ft² total solar glazing across all passive systems

These values are planning ratios; final sizing depends on climate, shading, thermal mass, and internal gains.

- Select glazing performance by façade and climate (U-factor and SHGC)

To select glazing, match solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) and U-factor to climate and orientation.

- SHGC meaning: SHGC is the fraction of solar energy transmitted through a window that becomes heat inside. ENERGY STAR describes SHGC as a 0–1 scale, typically 0.25 to 0.80, where lower values block more solar heat.

- NFRC rating infrastructure: ANSI/NFRC procedures determine SHGC and visible transmittance using the WINDOW and THERM software developed by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), under standardized conditions.

Practical façade logic:

- South (heating-dominated climates): higher SHGC can increase winter “passive energy gain,” but must be matched with mass and shading.

- East/West: lower SHGC and/or exterior shading controls morning/afternoon low-angle sun, which is harder to block with horizontal overhangs. WBDG notes horizontal overhangs are effective on south façades but less effective on west façades for low afternoon sun.

- Add thermal mass using glass-to-mass relationships and thickness limits

To add thermal mass, follow ratios that prevent large temperature swings and overheating.

NREL’s Portland guideline provides mass-to-glazing sizing relationships for direct gain:

- Add 1.0 ft² of direct-gain glazing per 5.5 ft² of uncovered, sunlit mass floor.

- Estimate “sunlit” floor mass area as up to ~1.5× the south window area.

- Add 1.0 ft² of glazing per 40 ft² of thermal mass floor area that is in the room but not in sun.

- Add 1.0 ft² of glazing per 8.3 ft² of thermal mass in walls/ceiling in the same room.

Thermal mass thickness has diminishing returns beyond a certain point:

- The same guideline reports effectiveness increases with thickness up to about 4 inches, then levels off; a 2-inch mass floor is about two‑thirds as effective as a 4-inch floor, while a 6-inch floor performs only about 8% better than a 4-inch floor.

- Design shading as a cooling-load control, not decoration

To design shading, align shading type with solar orientation and the cooling season.

WBDG reports that well-designed sun control and shading devices can reduce building peak heat gain and cooling requirements, and notes reported reductions in annual cooling energy of 5% to 15%, depending on fenestration amount and location.

Common control devices:

- Fixed roof overhangs for south windows

- Vertical fins for east/west façades

- Exterior blinds/shutters

- Light shelves that also improve daylight distribution

- Use ventilation as a designed heat-removal path

To use ventilation effectively, pair operable windows (or vents) with airflow paths.

DOE states well-designed passive solar homes use nighttime ventilation for cooling-season comfort.

- Refine with simulation when loads are low and risks are high

To refine design, use whole-building modeling and sun-path analysis.

DOE notes that a successful passive solar home needs details and variables in balance and that experienced designers can use a computer model to simulate different configurations until the design fits site, budget, and performance requirements.

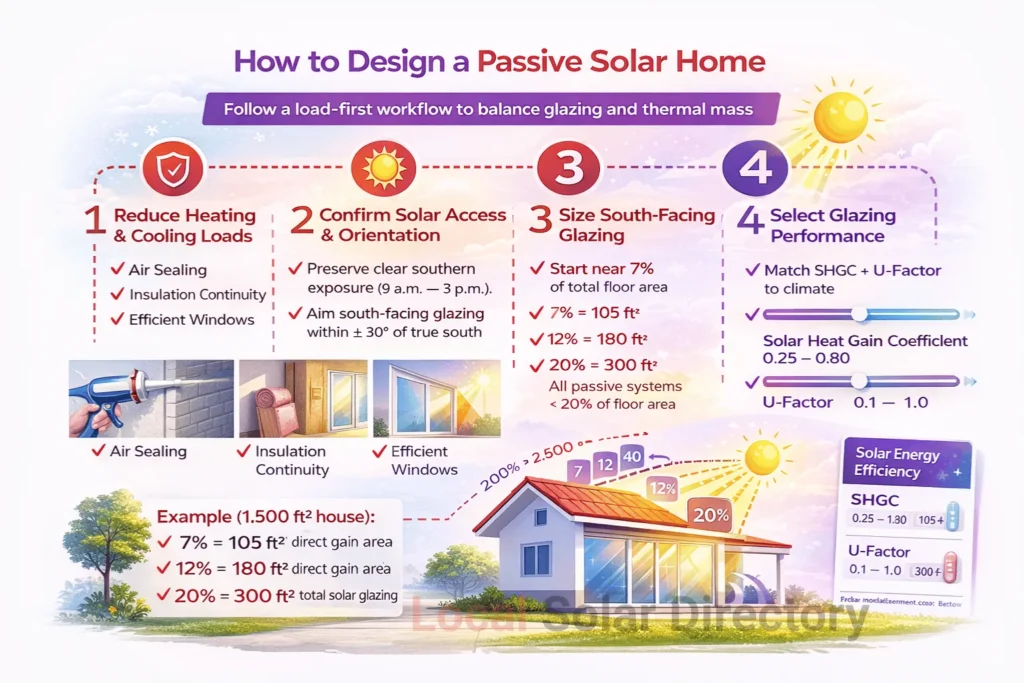

How Does Passive Solar Building Design Work?

Passive solar building design works by integrating orientation, façade-specific glazing/shading, envelope insulation/airtightness, thermal mass, daylighting, and natural ventilation to reduce HVAC and lighting loads at building scale. The Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP) describes passive solar strategies as the foundation of low-energy building designs and notes that in warm climates these strategies can reduce cooling loads, with measures such as overhangs controlling solar heat gain.

What changes when the building is commercial or institutional (vs a house)?

Passive solar principles are the same, but building-use patterns change the design constraints.

- Internal gains are often higher (people, lighting, equipment), so overheating risk from excess glazing can be higher even in cold climates.

- Occupied hours align with solar availability (daytime occupancy), so daylighting and solar heat gains can be more directly useful, but glare control is a bigger constraint.

- Floor plates are deeper, so daylighting and perimeter-zone heat gains must be coordinated with interior HVAC zoning.

Building-scale design moves with measured impacts (research findings)

A building-focused study in Applied Sciences (University of Pisa, Giacomo Cillari, Fabio Fantozzi, Alessandro Franco; published 2 January 2021) reported:

- Latitude and orientation changes affected energy savings on average by 3–13 and 6–11 percentage points, respectively.

- In the case study, ~20% of total building energy demand was saved using passive solar systems.

- Combining direct and indirect passive solutions cut about half of heating demand and about 25% of cooling energy demand.

Those results match the building-design logic used in federal guidance: passive solar strategies are designed as a whole-building system that coordinates envelope, glazing, shading, daylighting, and ventilation.

Common passive solar building elements (beyond the single-family toolkit)

- Perimeter daylighting + glare control (light shelves, exterior shading, high-performance glazing)

- Thermal mass placed in perimeter zones to buffer solar and internal gains

- Night ventilation / night flush to remove stored heat in mass (climate-dependent)

- Atrium or stack ventilation elements to enhance buoyancy-driven airflow

- Façade zoning: different glazing types by exposure (south vs east/west vs north), a practice explicitly described in NREL passive solar guidance (use different glazings by exposure).

What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Passive Solar Energy?

Passive solar energy provides lower heating and cooling energy demand, lower mechanical system capacity needs, and improved daylighting potential through building design, but it also introduces design constraints, overheating/glare risk, and performance sensitivity to site and climate. DOE and Building America guidance emphasize that success depends on proper glazing sizing, solar access, shading, and thermal-mass balance, and warn against oversizing south-facing glass in modern low-load homes.

- In homes, passive solar design can offset a measurable fraction of heating load (passive solar fraction) while maintaining comfort, if glazing is oriented and shaded properly and thermal mass is adequate.

- In commercial buildings, passive solar strategies also target daylighting and cooling-load reduction. WBDG reports that shading devices have documented annual cooling-energy reductions of 5%–15% in some cases, and FEMP notes passive solar can reduce cooling loads in warm climates.

Table: advantages, disadvantages, and the control that makes the difference

The table below lists the main pros/cons and the design control used to keep passive solar performance stable.

| Dimension | Advantages (measurable outcomes) | Disadvantages / risks (failure modes) | Primary control that mitigates the risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heating energy | Solar heat gain offsets heating load (“passive solar fraction”). | Heat loss through glazing at night can increase auxiliary heating demand. | Low U-factor glazing + night insulation strategies + mass sizing. |

| Cooling energy | Shading + ventilation reduce cooling loads; shading devices reported to cut annual cooling energy 5%–15% in some cases. | Overheating in shoulder seasons or summer if south glass is oversized or unshaded. DOE flags this risk directly. | Overhangs, exterior shading, low-SHGC glazing by exposure, nighttime ventilation. |

| Comfort (temperature swing) | Thermal mass dampens indoor temperature swings; mass effectiveness increases up to ~4 inches thickness. | Large indoor swings if glazing-to-mass ratio is wrong; NREL notes overheating if mass is undersized. | Use glass-to-mass ratios (e.g., 1 ft² glazing per 5.5 ft² sunlit mass floor). |

| Lighting energy (buildings) | Daylighting can reduce electric lighting demand; shading devices also improve daylight quality and reduce glare. | Glare and contrast problems; fabric fading noted as a concern when glazing is excessive. | Daylight controls, glare-control shading, glazing selection by exposure. |

| Mechanical system sizing | Building America notes reduced mechanical heating/cooling capacity needs can reduce equipment size and related costs over building life. | Higher first-cost for extra glazing, shading, and mass is possible; design time is higher. | Whole-building design optimization; energy modeling. |

| Site dependence | Uses local solar resource and orientation; can work with many architectural styles when site allows solar access. | Performance drops if solar access is blocked by trees/buildings; DOE notes solar access constraints and future shading risks. | Site planning, zoning/solar access planning, landscaping management. |

Diagram 2 : “Complete” passive solar system map (five elements + controls)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PASSIVE SOLAR SYSTEM = BUILDING ELEMENTS + CONTROL │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

(1) APERTURE / COLLECTOR (5) CONTROL (keeps gains useful)

South-facing glazing - Roof overhangs / exterior shading

(solar heat gain path) - Operable vents/dampers

│ - Low-e blinds / shutters / awnings

│ - Night ventilation strategy

▼

(2) ABSORBER (surface that captures heat)

Dark interior floor/wall surface

│

▼

(3) THERMAL MASS (stores heat, shifts time)

Concrete / brick / stone / tile / water / PCM

│

▼

(4) DISTRIBUTION (moves heat to where needed)

Conduction + convection + radiation

(sometimes assisted by small fans)

In Diagram 2, the system is complete only when (1) aperture, (2) absorber, (3) thermal mass, (4) distribution, and (5) control strategies work together. NREL describes these five elements explicitly (aperture/collector, absorber, thermal mass, distribution, control) and notes that passive solar types (direct, indirect, isolated gain) differ in how those elements are combined.

What Are the Components of Passive Solar Energy?

The components of a passive solar energy system are the aperture (collector), absorber, thermal mass, distribution, and control elements integrated into the building envelope and layout. NREL’s DOE-produced brochure defines these five elements and uses direct gain as the example configuration.

Component-by-component definition with examples and metrics

The table below defines each component and lists the most used design metrics.

| Component | What the component does | Typical home/building examples | Metrics that are commonly specified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aperture (collector) | Admits solar radiation into the building. | South-facing windows, clerestories, sunspace glazing | Orientation within ±30° of true south; solar access (e.g., unshaded 9 a.m.–3 p.m. heating season). |

| Absorber | Converts incoming solar radiation into heat at interior surfaces. | Dark floor tiles, masonry wall surfaces | Surface absorptance; exposure to sun patches |

| Thermal mass | Stores heat and releases it later; dampens temperature swings. | Concrete slab, brick/CMU interior walls, stone floors, water containers, phase-change products | Thickness effectiveness up to ~4 in; glass-to-mass ratios (e.g., 1 ft² glazing per 5.5 ft² sunlit floor mass). |

| Distribution | Moves heat from collection/storage zones to other areas. | Conduction through floors/walls; convective air movement; radiant exchange; sometimes small fans | Qualitative: convection paths, door/vent placement; fan-assisted distribution (hybrid) noted by DOE/NREL. |

| Control | Prevents overheating and manages seasonal performance. | Overhangs, exterior shading, operable vents/dampers, low-e blinds, shutters, landscaping | SHGC (0–1; typically 0.25–0.80); shading design by façade; night ventilation. |

A passive solar design also depends on basic envelope performance. DOE explicitly frames passive solar success as “energy efficiency first,” because lower loads make solar gains easier to use without overheating.

What Configurations Are Used to Build Passive Solar Systems?

The configurations used to build passive solar systems are direct gain, indirect gain, and isolated gain, and many buildings use hybrids that combine more than one configuration. Building America and NREL both group passive solar heating techniques into these three categories.

Direct gain (most common in houses)

Direct gain is a configuration where sunlight passes through glazing directly into the occupied space and is stored in interior mass. Building America defines direct gain as solar radiation that penetrates and is stored in the living space.

- Limit direct-gain south glazing to reduce glare and overheating risk; NREL’s guideline provides a 12% of floor area cap for direct gain and a 20% cap for all systems combined.

- Balance added glazing with added mass (example ratios in the home-design section).

See in image Direct Gain of passive Solar Heating

Indirect gain (thermal storage wall / Trombe wall / water wall)

Indirect gain is a configuration where solar radiation is collected and stored in a thermal storage element that then transfers heat to the interior by conduction, radiation, or convection. Building America describes indirect gain as collecting, storing, and distributing solar radiation using thermal storage material, giving the Trombe wall as an example.

Practical detailing (from NREL’s passive solar design strategies):

- For thermal storage walls, the space between glazing and thermal mass should be 1 to 3 inches.

- Double glazing is recommended for thermal storage walls unless a selective surface is used.

Isolated gain (sunspace)

Isolated gain collects solar radiation in an area that can be selectively closed off or opened to the rest of the building (for example, a sunspace). Building America uses “sunspace” as the example of isolated gain.

Isolated-gain benefits:

- Better control of heat flow (open/close) compared with direct gain

- Useful for daylighting and transitional spaces (climate-dependent)

Suntempering (a conservative subset often used in retrofits)

Suntempering is a conservative approach that uses modest increases in south-facing windows without extra thermal mass; NREL’s guideline distinguishes suntempered designs from full passive solar houses and explains that “free mass” may be enough for modest glazing increases.

The table below compares configurations on where heat is collected, stored, and controlled.

| Configuration | Where solar heat is collected | Where heat is stored | Main control method | Main risk if misdesigned |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct gain | Inside occupied space via south glazing | Interior floors/walls (thermal mass) | Overhangs, shading, mass sizing, ventilation | Overheating/glare; glazing-to-mass imbalance |

| Indirect gain (Trombe wall) | Behind glazing, at thermal storage wall | Thermal storage wall (masonry/water) | Vents/dampers, selective surfaces, glazing detail (1–3 in gap) | Heat delivery timing mismatch; summer overheating if unshaded |

| Isolated gain (sunspace) | In a separated sunspace | Sunspace mass + air volume | Open/close connection to main building | Overheating in sunspace; unwanted gains without separation |

What Is Active Solar Energy vs. Passive Solar Energy?

Active solar energy is solar energy captured by equipment (collectors, pumps, fans, controls, PV modules) that converts sunlight into usable heat or electricity, while passive solar energy is solar energy managed by building design (glazing, thermal mass, shading, ventilation) without powered equipment as the primary transport mechanism. DOE’s consumer guide states passive solar design does not use mechanical/electrical devices such as pumps and fans to move collected solar heat and instead uses windows, walls, and floors to collect, store, and distribute heat. The Difference you can also see in this image it explain most of the differences between active solar energy and passive Solar Energy.

Active solar energy systems

- Active solar space heating: DOE explains active solar heating systems use solar energy to heat a fluid (air or liquid) and transfer that heat to interior space or storage; fans or pumps move the fluid.

- Solar water heating (active): DOE describes active systems where pumps circulate water or a heat-transfer fluid through collectors and into the home (direct or indirect circulation).

- Photovoltaics (PV): convert sunlight directly to electricity (electrical, not thermal).

Passive solar energy systems

- South-facing windows + thermal mass (direct gain)

- Trombe wall / thermal storage wall (indirect gain)

- Sunspace (isolated gain)

Table: active vs passive solar (what actually differs)

| Attribute | Passive solar energy | Active solar energy |

|---|---|---|

| Primary “collector” | Building envelope (windows/walls/floors) | Solar collectors or PV modules |

| Heat transport | Natural conduction/convection/radiation; sometimes minimal fans (hybrid) | Pumps/fans move fluid/air through collectors and storage |

| Primary outputs | Space heating, cooling-load reduction, daylighting | Hot water, space heating, process heat, electricity (PV) |

| Main performance constraint | Site solar access + glazing/mass/shading balance | Collector sizing, pumping power, storage, controls, maintenance |

What Is the Difference Between Passive Solar Energy and Solar Thermal Energy?

Passive solar energy is a building-design approach that uses sunlight entering through glazing and stored in building mass to heat and cool spaces, whereas solar thermal energy uses solar collectors to heat a working fluid (water or air) for hot water, space heating, or other thermal uses. The U.S. Energy Information Administration explains that active solar heating systems move heated fluid (air or liquid) through collectors using pumps or fans, while DOE materials distinguish passive solar building design from active systems that use mechanical equipment.

Solar thermal systems can be active or passive depending on circulation:

- DOE’s solar water heater guidance describes active systems that use pumps (direct or indirect circulation).

- DOE also recognizes passive solar water heating systems (usually less expensive but typically less efficient than active systems).

So “passive” can describe either:

- Passive solar building design (space heating/cooling through architecture), or

- Passive circulation in solar thermal water heating (thermosiphon-type designs), which is still a solar thermal collector system.

Is Passive Solar Energy Used for Heating and Cooling?

Passive solar energy is used for heating by maximizing winter solar heat gain and storing it in thermal mass, and it is used for cooling by minimizing unwanted solar gains and removing heat through shading and ventilation. DOE describes passive solar homes as warming in winter and blocking solar heat in summer, and FEMP notes passive solar design can reduce cooling loads in warm climates using measures such as overhangs.

Passive solar heating (what is done)

Passive solar heating is achieved through these mechanisms:

- Oriented glazing: collector glazing within ±30° of true south and unshaded during heating season.

- Balanced glazing area: start near 7% of floor area for direct gain; limit direct gain near 12%; limit total passive solar glazing near 20% (planning ratios from NREL guideline).

- Thermal mass: store heat during the day and release it later; mass effectiveness increases up to ~4 inches thickness.

- Distribution: conduction, convection, radiation move heat to cooler zones.

Passive solar cooling (what is done)

Passive solar cooling is achieved through these mechanisms:

- External shading: reduces solar heat gain; WBDG reports 5%–15% annual cooling-energy reductions in some cases using sun control and shading devices.

- Façade-specific glazing: lower SHGC where cooling is dominant or where low-angle sun is difficult to shade; ENERGY STAR notes SHGC typically ranges 0.25–0.80 and lower SHGC transmits less solar heat.

- Night ventilation: DOE notes nighttime ventilation as part of well-designed passive solar homes for cooling-season comfort.

- Thermal mass as a heat buffer: mass absorbs heat during the day and can be “reset” by night flushing (climate-dependent).

A practical “heating + cooling” rule set that prevents common failures

- Keep glazing sized (avoid oversizing south glass) and shaded; DOE flags oversizing risk in modern low-load homes.

- Keep thermal mass exposed where sun hits it; NREL notes carpet/rugs reduce mass effectiveness for sunlit floors.

- Use exterior shading where possible; WBDG describes external shading as an excellent way to prevent unwanted solar heat gain from entering conditioned space.