5 Main Types of Solar Energy: Advantages and Disadvantages

I Explain 5 Main Types of Solar Energy. Passive Solar Energy, Solar thermal energy, Concentrated Solar Power (CSP), Photovoltaic (PV), and Building‑Integrated PV (BIPV).

The table below compares the 5 solar energy types by output form, core hardware, and the most common technical limitation.

| Solar energy type | Output form | Core hardware | Typical scale | Key advantage | Key disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive solar energy | Heat + daylight reduction in building demand | Building orientation, glazing, thermal mass, shading | Single building | Low operating complexity | Design constraints + overheating risk |

| Solar thermal energy | Heat (hot water / space heat / process heat) | Collectors + fluid loop + storage | Building to district | High conversion to heat at low temperature lift | Freeze/overheat control + heat-only output |

| Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) | Electricity (via heat engine) + optional thermal storage | Mirrors/heliostats + receiver + turbine | Utility-scale (commonly ≥50 MW) | Thermal storage enables dispatchable output | Needs high direct sunlight (DNI) + higher complexity |

| Photovoltaic (PV) | Electricity (DC → AC via inverter) | PV modules + inverters + BOS | From watts to gigawatts | Modular, low O&M, fast deployment | Variability + grid integration and storage needs |

| Building‑Integrated PV (BIPV) | Electricity + building envelope function | PV in roof/facade/glazing products | Building | Produces power without separate racks | Higher design/installation complexity |

Passive Solar Energy

Passive solar energy is solar heat and daylight managed by building design elements, without relying on mechanical devices to move heat.

What passive solar energy is

Passive solar design captures winter sun and blocks summer sun through layout, materials, and shading features. DOE’s passive solar guidance defines passive systems as using windows, walls, and floors to collect, store, and distribute solar heat, while avoiding pumps, fans, and electrical controls as the primary heat‑moving mechanism.

Core passive design elements (5): aperture (glazing), absorber surface, thermal mass, heat distribution paths, and control (shading/overhangs).

Where passive solar energy is used

Passive solar energy is used in building design and retrofits where space heating/cooling loads can be reduced through geometry and materials.

- Residential buildings: sun‑tempered layouts, direct‑gain rooms, thermal‑mass floors, exterior shading.

- Commercial buildings: daylighting with glare control, atriums, thermal‑mass strategies, façade shading.

- Any climate zone: DOE guidance notes passive techniques apply across climate zones, with design choices changing by heating vs cooling dominance.

Advantages of passive solar energy

Passive solar advantages are driven by building physics and low equipment dependence.

- Reduces heating demand through direct solar gains.

- Reduces lighting demand through daylighting, which also reduces internal heat from electric lighting.

- Low mechanical complexity: fewer moving parts than pumped thermal systems.

- Long service life: building elements (masonry, glazing, overhangs) have multi‑decade lifetimes when maintained as envelope components.

- Resilience: indoor temperature drift slows when thermal mass and insulation are designed as a system.

- South orientation tolerance: DOE passive-solar homebuilding guidance reports that a building facing within ~30° of true south retains about 90% of optimal winter solar gain.

- Glazing performance targets (examples used in DOE guidance): high solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) glazing for south windows in heating climates and low U‑factor windows in colder climates.

- Solar transmission of clear glass: the DOE passive solar guide notes clear glass transmits nearly 90% of the sun’s heat, which explains why glazing selection and shading control dominate outcomes.

Disadvantages of passive solar energy

Passive solar disadvantages are constraints imposed by climate, site geometry, and occupant behavior.

- Site dependence: shading from buildings/trees reduces usable winter gains.

- Overheating risk: oversized glazing or insufficient summer shading increases cooling loads.

- Design constraints: orientation, room layout, and façade design can constrain architecture and lot usage.

- Retrofit limitations: major passive gains often require envelope changes (window placement, insulation, thermal mass), which are harder than adding rooftop PV.

- Control granularity: passive systems control heat indirectly through shading, ventilation, and mass; fine‑tuned control requires active components.

How do the installations work to obtain active solar energy?

Installations obtain active solar energy by adding mechanical or electrical devices that capture and move solar energy, such as pumps, fans, or power electronics, instead of relying only on passive heat transfer.

Practical pathways from passive to active on a building:

- Add a solar thermal collector loop (pump + controller + storage tank) to actively harvest heat for hot water or space heating.

- Add photovoltaic modules + inverter to actively convert sunlight to electricity.

- Add fan‑assisted solar air heating or ventilation preheat (fan + ductwork) to move heated air where needed.

Definition of active solar energy: Active solar energy is solar energy collected and converted using mechanical or electrical equipment—examples include circulating pumps and controls in solar thermal systems and inverters in photovoltaic systems.

Solar Thermal Energy

Solar thermal energy is solar radiation converted into usable heat by collectors that warm a working fluid (water, glycol mix, or air) for hot water, space heat, or industrial thermal loads.

What solar thermal energy is

Solar thermal systems use a collector to absorb sunlight and transfer heat into a fluid that feeds a storage tank or a heat exchanger.

Common collector families (building-scale):

- Flat‑plate collectors (glazed or unglazed)

- Integral collector-storage (ICS / batch) systems

- Evacuated‑tube collectors

Collector selection tracks required temperature lift:

- Pool heating uses unglazed collectors because the target temperature is near ambient, minimizing heat loss penalties.

- Domestic hot water usually requires water temperatures ~30–40 °C above ambient in many conditions, increasing the importance of insulation and heat loss control.

Where solar thermal energy is used

Solar thermal energy is used where heat demand is significant and predictable.

- Domestic hot water (DHW): bathrooms, kitchens, laundries.

- Space heating support: hydronic systems, air handlers, solar air heaters.

- Pool heating: unglazed polymer collectors are common because of low temperature lift.

- Commercial hot water loads: hotels, hospitals, dormitories, laundries.

- Industrial process heat (low to medium temperature): preheating, washing, drying, and other thermal steps.

Advantages of solar thermal energy

- High conversion to heat at low temperature lift: converting sunlight to heat avoids the thermodynamic and semiconductor limits of electricity conversion.

- Direct match to heat demand: domestic hot water is a daily load in most buildings.

- Thermal storage simplicity: hot water tanks store energy directly as sensible heat.

- Low noise and low operational complexity compared with engine-based thermal cycles.

Independent test datasets highlight how efficiency changes with temperature difference:

- A document quoting Solartechnik Prüfung Forschung (SPF) testing on 160+ collectors reports average gross collector efficiency around 70% for flat‑plate collectors and 49% for evacuated‑tube models under low-to-medium temperature difference conditions, with wide ranges across products.

(Collector efficiency depends strongly on ΔT between collector and ambient; higher ΔT increases losses.)

Disadvantages of solar thermal energy

- Heat-only output: solar thermal does not directly supply electricity.

- Freeze risk and stagnation risk: cold climates drive indirect loops (glycol + heat exchanger), while hot climates require overheat control.

- Roof and plumbing integration complexity: roof penetrations, piping insulation, pump/controller wiring, and water quality management.

- Maintenance requirements: pumps, valves, heat-transfer fluid replacement intervals, pressure relief devices.

- Seasonal mismatch: peak solar resource often occurs when space-heating demand is lower (cooling-dominant climates).

How do the installations work to obtain active solar energy?

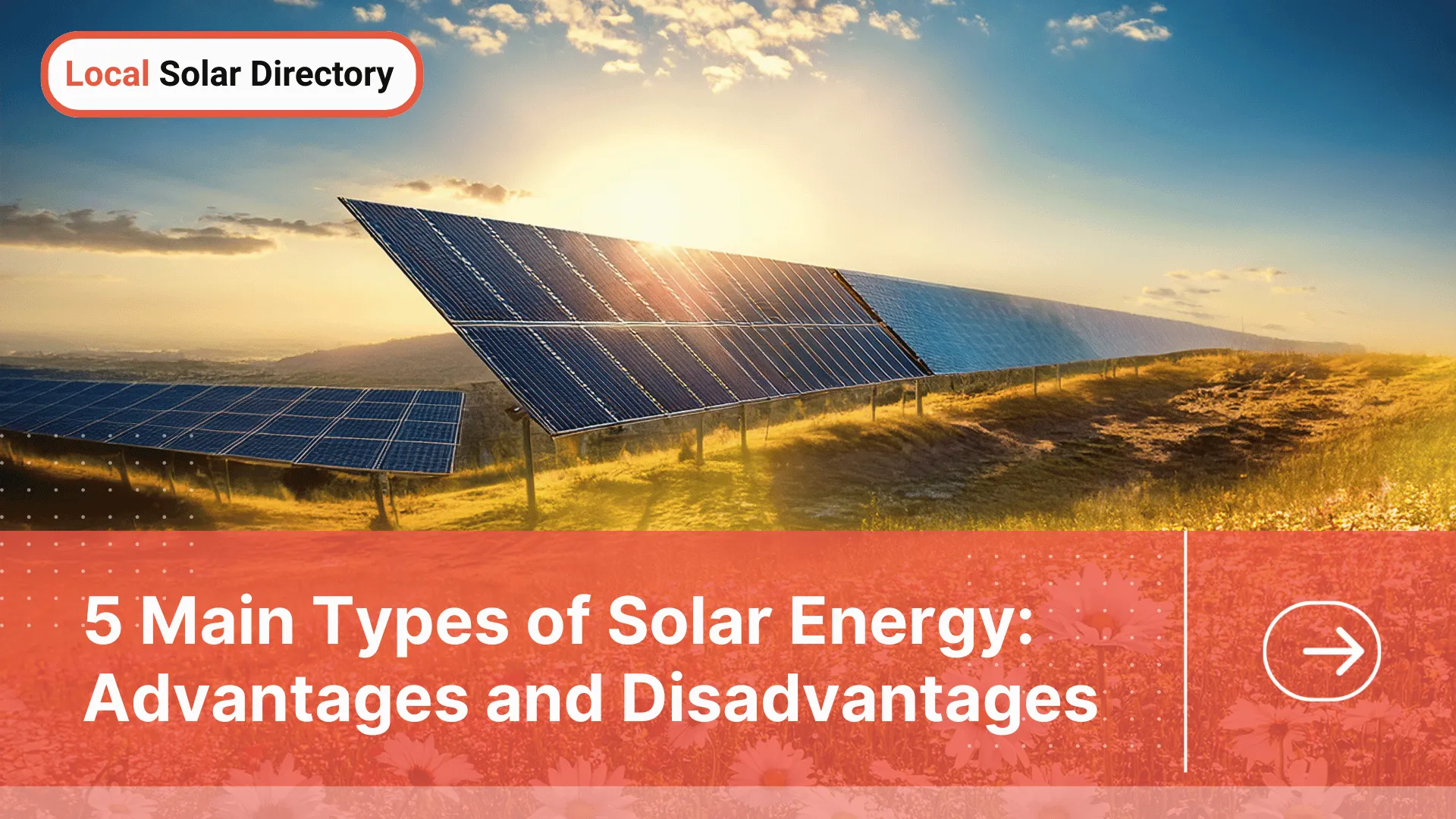

Installations obtain active solar energy in solar thermal systems by using collectors, circulating pumps, and controls to move heat from the collector to storage and then to end uses.

Typical active solar thermal installation flow:

- Collector absorbs sunlight and heats the collector loop fluid (water or heat-transfer fluid).

- Controller triggers circulation when collector temperature exceeds tank temperature (differential control logic is common).

- Pump circulates fluid through the collector loop.

- Heat exchanger transfers heat to potable water in the storage tank in indirect systems.

- Storage tank holds thermal energy for use outside peak sun hours.

- Backup heater covers shortfalls (electric, gas, or heat pump) during low solar periods.

Active system types in DOE guidance:

- Direct circulation systems: pumps circulate household water through collectors; used where freezing is rare.

- Indirect circulation systems: pumps circulate non-freezing heat-transfer fluid through collectors and a heat exchanger; used in freeze-prone climates.

I attach image to explain How installations work to obtain active solar energy.

Solar thermal vs PV (paragraph)

Solar thermal converts sunlight into heat, while photovoltaic (PV) converts sunlight into electricity. Solar thermal collectors often reach higher instantaneous conversion to usable energy when the end use is low-temperature heat (for example, water heating), because the system avoids inverter and electrical conversion losses; PV produces electricity that can serve many loads, but PV electricity often requires storage or grid balancing for night-time use. PV module efficiencies for commercial crystalline silicon modules center in the low‑20% range in recent manufacturer data, while solar thermal collector efficiency varies widely and drops as temperature lift increases due to heat loss physics. you can see the full comparison Solar thermal vs PV

Concentrated Solar Power (CSP)

Concentrated solar power (CSP) uses mirrors to focus sunlight, heat a working fluid, and run a turbine-generator to produce electricity.

What concentrated solar power (CSP) is

NREL describes CSP as focusing and intensifying sunlight, absorbing the energy to heat a fluid, and using that heat to drive a turbine connected to a generator.

Primary CSP configurations:

- Parabolic trough: mirrors focus sunlight onto a linear receiver tube.

- Power tower (central receiver): heliostats reflect sunlight to a receiver on a tower.

NREL also notes linear Fresnel and dish-engine systems as additional configurations, but less common.

Where CSP is used

CSP is used in utility-scale electricity generation where direct normal irradiance (DNI) is high and land is available.

Typical deployment characteristics:

- Utility scale: NREL’s CSP fact sheet states CSP is typically constructed at utility scale, commonly 50 MW or greater.

- High-DNI regions: deserts and semi-arid climates enable higher performance because CSP concentrates direct sunlight.

Advantages of CSP

- Thermal storage compatibility: CSP “inherently lends itself to energy storage” because heated fluids or molten salt can be stored and used later to produce electricity.

- Higher capacity factor than PV in storage-equipped designs: storage shifts output into evenings and reduces curtailment risk.

- High-temperature heat: tower systems often operate at higher temperatures than trough systems; NREL reports typical operating temperatures around 565 °C for power towers and ~390 °C for parabolic troughs.

- High storage round-trip efficiency (thermal): NREL reports storage round-trip efficiency around ~99% for molten-salt towers in the referenced fact sheet context.

Disadvantages of CSP

- Solar resource constraint: CSP performance depends on direct sunlight; diffuse light from clouds does not concentrate efficiently.

- Higher system complexity: heliostat tracking, high-temperature receivers, heat exchangers, turbine island, and thermal storage systems add engineering and O&M complexity.

- Water use and siting constraints: NREL notes CSP projects tend to require more water for operations and need proximity to substations, affecting siting.

- Cost trajectory: the same NREL fact sheet notes CSP costs have not declined as quickly as solar PV costs (technology and market context specific).

How do the installations work to obtain active solar energy?

Installations obtain active solar energy in CSP by using tracking mirrors to concentrate sunlight, heating a working fluid, and converting that thermal energy into electricity through a turbine-generator system.

A power tower CSP system with molten-salt storage follows a typical flow:

- Heliostats track the sun and reflect sunlight to a receiver on a tower.

- Receiver heats molten salt (or another heat-transfer fluid) to high temperature.

- Hot tank stores thermal energy in a two-tank system (hot/cold tanks).

- Heat exchanger produces steam from the hot fluid, then steam drives a turbine-generator.

- Cooled fluid returns to the cold tank and recirculates.

Example with published operational detail (Gemasolar, Spain):

Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) documented the Gemasolar power tower plant as 19.9 MW (gross), using a two-tank molten salt storage system with up to 15 hours capacity, designed for expected net capacity factors near 75%, and operating molten salt temperatures around 565 °C with return around 290 °C.

Photovoltaic (PV)

Photovoltaic (PV) solar energy is electricity generated when photovoltaic cells convert sunlight directly into direct-current (DC) electricity through a semiconductor device.

What photovoltaic (PV) solar energy is?

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) defines a PV cell as a nonmechanical device that converts sunlight directly into electricity, using photons from sunlight.

PV system output passes through power electronics:

- PV modules produce DC electricity.

- Inverters convert DC to AC for the grid and building loads; DOE describes the inverter as a key device that converts PV DC electricity into AC electricity used by the grid.

Where PV is used?

PV is used across nearly every scale because modules are modular.

Common deployment modes:

- Residential rooftop PV: 3–20 kW typical range by market, roof area, and load.

- Commercial/industrial PV: rooftops, carports, ground-mount.

- Utility-scale PV: tens to hundreds of megawatts per site.

- Off-grid PV: telecom sites, remote microgrids, water pumping, cabins.

What are the Advantages of PV?

The Advantages of PV are:

- Modularity and scalability: PV arrays scale from a single module to utility plants.

- Low operating noise and low moving-part count: fixed-tilt PV has no trackers; tracker systems add motion but remain lower complexity than thermal cycles.

- Fast construction: balance-of-system is largely racking + wiring + inverter interconnection.

- Efficiency improvements in commercial modules: Fraunhofer ISE reported that commercial monocrystalline wafer-based silicon modules increased from about 16% to values over 24% over the last decade, with CdTe module efficiency rising from ~9% to almost 20% in the same period.

- Current commercial efficiency distribution: Fraunhofer ISE reported a total weighted average efficiency of 22.7% for crystalline silicon modules in Q4‑2024, with low and high values in the cited dataset of 18.9% to 24.8%.

- Low life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions relative to fossil generation: NREL’s LCA Harmonization Project fact sheet reports median life-cycle emissions for PV technologies below 50 g CO₂e/kWh after harmonization.

What Are The Disadvantages Of PV?

Tthe Disadvantages of PV are:

- Variability: output drops at night and during heavy cloud cover; variability requires grid flexibility, storage, or complementary generation.

- Temperature sensitivity: module power drops as cell temperature rises (technology dependent).

- Land and siting constraints at utility scale: land use, habitat, and visual impacts require planning and permitting.

- Supply chain and end-of-life: PV deployment raises materials sourcing and recycling logistics; recycling infrastructure varies by region.

- Power electronics dependency: grid-tied PV requires inverters and protection systems, and grid standards govern interconnection behavior.

How do the installations work to obtain active solar energy?

Installations obtain active solar energy in PV systems by converting incident solar radiation into DC electricity in modules and converting that DC electricity into usable AC power using inverters and grid interconnection equipment.

A typical grid-connected PV installation works as follows:

- Modules generate DC power from sunlight (series/parallel strings).

- Maximum power point tracking (MPPT) is performed in the inverter (or optimizer) to operate modules at the voltage/current that maximizes power under current irradiance and temperature.

- Inverter converts DC to AC and synchronizes to grid voltage and frequency.

- AC disconnect + breaker panel interconnect deliver power to on-site loads and/or export to the grid.

- Metering and monitoring measure production and export per utility rules.

You can see Also in image.

Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV)

Building‑integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) are PV materials that replace conventional building materials and generate electricity as part of the building envelope.

What BIPV is

DOE’s Solar Energy Technologies Office describes BIPV as emerging solar applications that replace conventional building materials with solar energy generating materials in the structure, including roofs, skylights, balustrades, awnings, facades, or windows.

The Whole Building Design Guide (WBDG) describes BIPV as PV collectors that are an integral part of the building envelope and lists examples such as PV glass windows, PV skylights, awnings, balustrades, canopies, shingles, and exterior wall panels.

Where BIPV is used

BIPV is used when the building envelope is designed to act as both cladding and generator.

Typical applications:

- New construction: integrated roofs and façades where envelope replacement value offsets part of PV cost.

- Architectural façades: curtain walls, spandrel panels, sunshades.

- Skylights and glazing: semi-transparent PV products for daylight + generation (product-dependent).

Advantages of BIPV

- Dual-function surfaces: one component provides weather barrier/cladding plus electricity generation.

- Reduced need for rack-mounted arrays: roof aesthetics and wind loading constraints can be reduced when PV is embedded into the envelope geometry.

- Distributed generation near loads: façade or roof production feeds building loads directly.

- Design flexibility for constrained rooftops: vertical surfaces add generation area when roof space is limited.

Disadvantages of BIPV

- Higher design complexity: waterproofing, drainage planes, thermal expansion, and code compliance interact with electrical design.

- Maintenance and replacement constraints: envelope-integrated modules are harder to replace than rack-mounted modules.

- Performance constraints: façade orientation, shading, and reduced rear ventilation can reduce yield relative to optimally tilted rooftop arrays.

- Product variability: BIPV products vary widely in electrical ratings, fire performance, and building code approval pathways.

How do the installations work to obtain active solar energy?

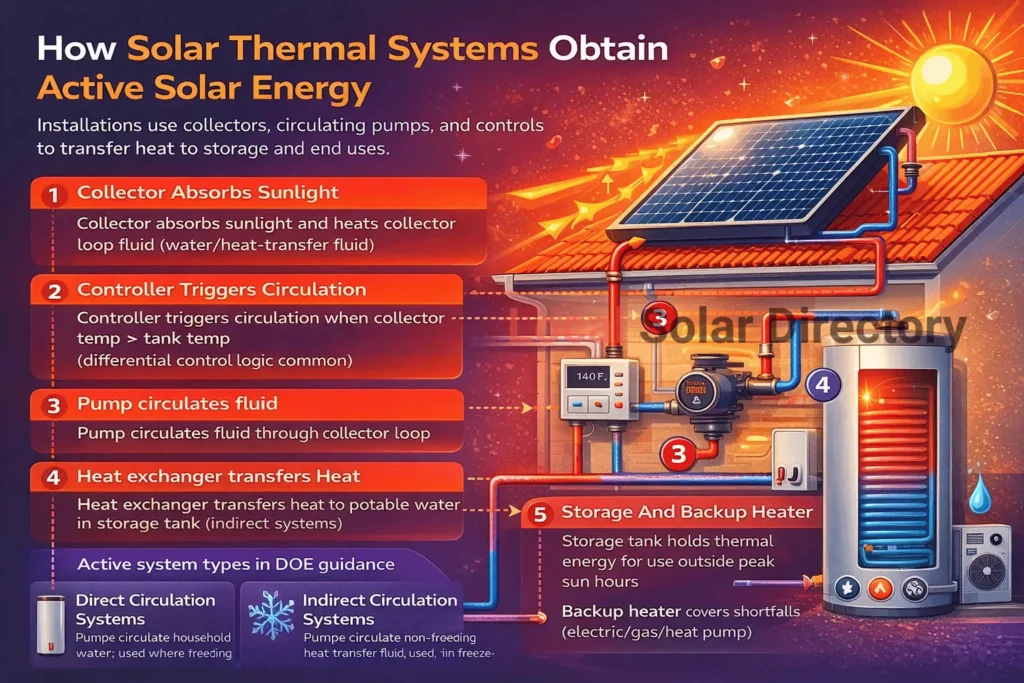

Installations obtain active solar energy in BIPV by integrating PV laminates or modules into roof/facade/glazing assemblies, wiring them as an electrical generator, and connecting the output to inverters and building electrical systems.

A typical BIPV electrical + envelope integration path:

- Envelope element selection: PV shingles, PV façade panels, or PV glazing selected as building skin.

- Waterproofing and air barrier integration: seams, flashing, and drainage detail aligned with PV product mounting.

- DC wiring routing inside envelope: concealed conduit paths designed to maintain fire and moisture barriers.

- Inverter connection: inverter converts DC to AC for building loads and/or grid export.

- Commissioning: insulation resistance tests, IV curve checks, grounding verification, and monitoring activation.

What are the types of solar energy systems?

Types of solar energy systems are passive solar systems, solar thermal systems, photovoltaic (PV) systems, concentrated solar power (CSP) systems, and hybrid solar systems that combine two conversion paths.

The table below classifies solar energy systems by conversion method and typical end-use, so the system type matches the required energy form (heat vs electricity).

| Solar system type | Solar conversion path | Typical end-use | Typical components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive solar building system | Sunlight → heat/daylight demand reduction | Space heating/cooling load reduction | Orientation, glazing, shading, thermal mass |

| Active solar thermal system | Sunlight → heat in fluid | DHW, space heat, pool heat, process heat | Collector, pump, controller, storage tank, heat exchanger |

| PV electricity system | Sunlight → DC electricity → AC | Building loads, grid export, microgrids | PV modules, inverter(s), racking, wiring |

| CSP electricity system | Sunlight → concentrated heat → steam turbine → electricity | Utility electricity, dispatchable output with storage | Mirrors/heliostats, receiver, turbine, thermal storage |

| Hybrid PV‑T system | Sunlight → electricity + heat | Electricity + low-temp heat | PV + thermal collector in one assembly (design dependent) |

| Solar‑plus‑storage system | Sunlight → electricity/heat + stored energy | Evening supply, backup, grid services | PV or CSP + batteries or thermal storage |

Architecture variants that are commonly used in practice:

- Grid-tied PV: exports to grid via inverter interconnection.

- Off-grid PV: pairs PV with batteries and/or generator in a microgrid.

- Hybrid (grid + storage): PV plus batteries to reduce peak demand and provide resilience.

What are the types of solar energy storage systems?

Types of solar energy storage systems are electrochemical storage (batteries), thermal storage (hot water, molten salt, phase-change), mechanical storage (pumped hydro, compressed air), and chemical storage (hydrogen and synthetic fuels).

The table below summarizes storage types that are commonly paired with solar, with duration and efficiency values from published operational statistics when available.

| Storage type | Stores energy as | Typical discharge duration | Representative round‑trip efficiency | Solar pairing use case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium-ion / utility batteries | Electrochemical | ~0.5–4+ hours (project dependent) | EIA reported ~82% average monthly round-trip efficiency for U.S. utility-scale battery fleet (2019). | PV ramp control, peak shaving, shifting mid-day PV to evening |

| Pumped-storage hydropower | Gravitational potential | 4–12+ hours | EIA reported ~79% average monthly round-trip efficiency for pumped storage (2019). | Grid-scale solar balancing, seasonal/long-duration support when available |

| Hot water tanks | Sensible heat | Hours to days | Application-specific (thermal losses dominate) | Solar thermal DHW + space heat buffers |

| Molten-salt (CSP TES) | Sensible heat in salts | 6–15+ hours | EPRI documented thermal storage efficiency >99% for the Gemasolar molten salt system (thermal cycle efficiency differs from storage efficiency). | Dispatchable CSP output into evening/night |

| Phase-change materials (PCM) | Latent heat | Hours | Application-specific | Building HVAC load shifting, solar thermal smoothing |

| Hydrogen (power‑to‑gas) | Chemical energy | Days to seasonal | Low in power→power pathways (electrolysis + reconversion losses) | Long-duration storage where electricity reconversion is required |

Practical solar-storage matching rules (engineering logic):

- Solar thermal collectors + hot water tank fits domestic water heating because storage is the same energy form (heat).

- PV + batteries fits electrical loads because storage is electrical form and inverter integration is standardized.

- CSP + molten salt fits dispatchability because thermal storage is integrated into the plant heat cycle.

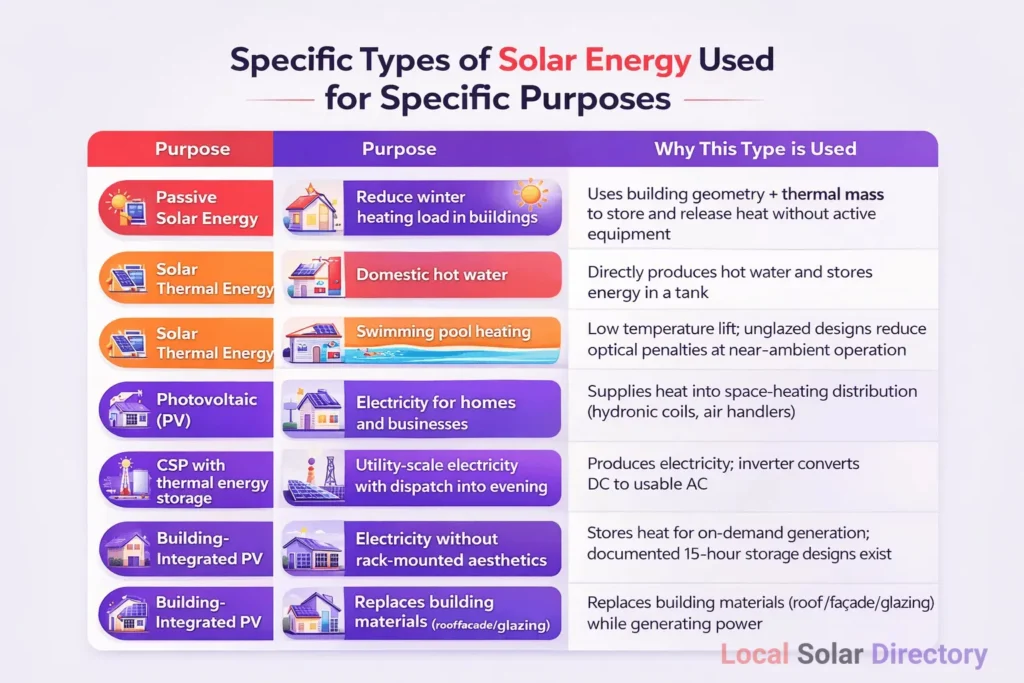

What are the specific types of solar energy used for specific purposes?

The specific types of solar energy used for specific purposes are passive solar (building heat/daylight demand reduction), solar thermal (heat for water/space/process), photovoltaic (electricity for loads and grids), CSP (utility electricity with thermal storage), and BIPV (electricity from envelope surfaces). I attach image also for more understanding.

The table below maps end-use purpose to the most common solar technology choice, based on matching the required energy form (heat vs electricity) and the physical constraints (site, envelope, solar resource).

| Purpose | Specific solar type used | Why this type is used (energy-form match) |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce winter heating load in buildings | Passive solar energy | Uses building geometry + thermal mass to store and release heat without active equipment |

| Domestic hot water | Solar thermal (flat-plate / evacuated tube / ICS) | Directly produces hot water and stores energy in a tank |

| Swimming pool heating | Solar thermal (unglazed collectors) | Low temperature lift; unglazed designs reduce optical penalties at near-ambient operation |

| Space heating support | Solar thermal + hydronic/air systems | Supplies heat into space-heating distribution (hydronic coils, air handlers) |

| Electricity for homes and businesses | Photovoltaic (PV) | Produces electricity; inverter converts DC to usable AC |

| Utility-scale electricity with dispatch into evening | CSP with thermal energy storage | Stores heat for on-demand generation; documented 15-hour storage designs exist |

| Electricity without rack-mounted aesthetics | BIPV | Replaces building materials (roof/facade/glazing) while generating power |

| Solar electricity forecasting and yield estimation | PV modeling tools (system-level) | NREL PVWatts estimates grid-connected PV production from location and system inputs |